Tagged: legal-liability

Nuisance and Tort Actions and Liability for Knotweed Infestations, Part 3 of 3 Part Series

The only reported case in the United States as of 2025 dealing with invasive knotweed as a private nuisance is Inman v. Scarsdale Shopping Center, 2013 NY Slip Op 3001 (NY S. Ct. 2016). In this case out of New York, a shopping center allowed Japanese knotweed to spread from its premises onto residential property owned by the Inmans. The Inmans, brought an action for negligence and private nuisance. A jury awarded the Inmans $535,000 plus interest. Unfortunately, the available legal opinions in Inman have limited factual details and legal analysis.

The only reported case in the United States as of 2025 dealing with invasive knotweed as a private nuisance is Inman v. Scarsdale Shopping Center, 2013 NY Slip Op 3001 (NY S. Ct. 2016). In this case out of New York, a shopping center allowed Japanese knotweed to spread from its premises onto residential property owned by the Inmans. The Inmans, brought an action for negligence and private nuisance. A jury awarded the Inmans $535,000 plus interest. Unfortunately, the available legal opinions in Inman have limited factual details and legal analysis.

Note at the outset that Inman involved a private nuisance action. A public nuisance is very different and usually affects the public broadly. In this article, I only discuss private nuisance actions.

Before diving into the specifics of the Inman case, I point out one kind of legal claim that was not brought in Inman, a trespass claim. Trespass claims resemble nuisance claims but have differences.

Trespass or Other Torts: Trespass is often pled in environmental actions. See Roisman AZ, Wolff A, “Trespass by Pollution: Remedy by Mandatory Injunction,” 21 Fordham Environ. L. Rev., 157 (2010). Bringing a trespass claim can have advantages over nuisance claims especially when seeking injunctive relief or overcoming statute of limitations requirements. Id. at 161-183. However, as one commentator has pointed out, courts in the United States have been reluctant to base their decisions concerning encroaching tree roots on trespass doctrine. LB Lea, “Nuisance-Liability for Injury Caused by Encroaching Tree Roots,” 46 Mich L. Rev. 997 (1948). The same reluctance could be true for invasive knotweed.

At the very least it makes sense for a plaintiff to include a claim based on trespass in addition to nuisance and negligence. In this article, I will try to point out areas where a trespass claim might lead to a different result than a nuisance or negligence claim.

Nuisance and Negligence: To establish a cause of action for private nuisance, the plaintiff must show that the defendant’s conduct causes substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of plaintiff’s land and that defendant’s conduct is (1) intentional and unreasonable, (2) negligent or reckless, or (3) actionable under the laws governing liability for abnormally dangerous conditions or activities. Copart Industries, Inc. v. Consolidated Edison Co., 41 N.Y.2d 564 (N.Y. 1977). In most cases involving invasive knotweed the key questions will be:

1. Did the defendant’s conduct substantially interfere with the use and enjoyment of the plaintiff’s land?

2. Was the defendant’s conduct negligent or reckless?

Let’s look at element no. 1 first. One way to effectively prove the first element is to show that the nuisance was a nuisance per se.

Nuisance Per Se: The Inman case does not address what is called a nuisance per se. However, a nuisance per se could readily arise in a nuisance case involving invasive species. If a party acts in a way that violates an ordinance or statue, that action may be considered a “nuisance per se.” For example, there are many cases dealing with the emission of pollutants from smokestacks that violated city ordinances. These smokestack emissions were often found to be a nuisance per se. See, e.g., State v. Chicago, M. & St. P. Ry., 114 Minn. 122, 130, 130 N.W. 545, 548(1911) (emission of dense smoke in city railroad yard, in violation of city ordinance prohibiting such emissions, held to be a nuisance per se).

To establish a nuisance per se, the plaintiff would need to prove: a violation of the statute, that the harm caused by the defendant was of a kind the statute was intended to prevent, and that the plaintiff was someone who the statute was intended to protect. See Cornell Law School, Legal Institute, Negligence Per Se, Reviewed August 2023.

New York has an Invasive Species Law. 6 CRR-NY 575.3. That law covers three species of invasive knotweed. However, that New York statute appears to only regulate the sale and transport of those species. In my reading, it doesn’t seem to address the spread of knotweed from one person’s property to another, i.e., the situation involved in Inman. Therefore, the New York Invasive Species Law would not appear to be intended to prevent the harm caused by the defendant in Inman.

Many other states, however, have statutes or ordinances that may address the typical homeowner invasive weed situation. For example, the Minnesota Noxious Weed Law, Minn. Stat. 18.75 (2025), lists two species of invasive knotweed as “Prohibited Control” species. Prohibited Control “species must be controlled to prevent the maturation and spread of propagating parts” (emphasis added). This statute seems directly relevant to the spread of invasive knotweed from one person’s property to another.

Other states like Colorado have a more stringent requirement for certain invasive knotweed species. In Colorado, certain species of knotweed are “prohibited” which means those species must be eradicated. Therefore, if the Inman case had arisen in either Minnesota or Colorado, it is very possible a court would have found a nuisance per se.

Still other kinds of laws might be implicated. For example, some local ordinances deal generally or very specifically with certain types of weeds. See, e.g., Sultan v. King, 73 Misc 3d 338 (NY 2021) (citing several of the ordinances on Long Island that “prohibit the maintenance of running bamboo.”). Commentators in Florida argue that a Florida statute concerning “sanitary nuisances” should in some cases apply to nuisances created by trees. Greenwald SJ, Van Treese JW II, Olexa MT, Brock CM, “Nuisance Trees: The Massachusetts or Hawaii Rule?”, 96 Florida Bar J, 32 (2022). These provisions could form the basis of a nuisance per se claim.

If there is no relevant statute that could establish a nuisance per se, what does the plaintiff have to prove to satisfy the first element showing that there is a substantial interference?

Substantial Interference with Use and Enjoyment of One’s Land: Did the defendant’s conduct substantially interfere with the use and enjoyment of the plaintiff’s land? Ultimately courts ask a series of questions that include “[1] whether the plaintiff had the property before the nuisance began, [2] the level of harm versus the usefulness of the defendant’s activity, and [3] whether the action would be annoying to the average person.” Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, Nuisance (Reviewed August 2023).

The first subpart, “whether the plaintiff had the property before the nuisance began,” is a holdover from the old common law doctrine that barred a nuisance claim when the plaintiff “came to the nuisance.” See, e.g., East St. Johns Shingle Co. v. Portland, 195 Ore. 505, 246 P.2d 554 (1952)(a narrow holding that the plaintiff’s claim against a municipality was barred because the plaintiff came to the nuisance). Today it appears that most courts follow the restatement and consider “coming to the nuisance” as a factor. See Restatement (2d) of Torts, § 840D.

I could see this factor of “coming to the nuisance” as being important in nuisance claims involving invasive species. For example, if a person moved to a location that was already infested with invasive knotweed, a court might say the buyer likely received a lowered real estate price because of the infestation. Moreover, once the buyer became the owner of the property, that owner now owned a property with a nuisance-causing infestation. In Minnesota or Colorado that new owner might be obligated to control the invasive knotweed on the owner’s property.

Is the “action” “annoying to the average person”? This is the factor that most courts would likely focus on in an invasive species nuisance case (other than one involving a nuisance per se).

We know that the factfinder in Inman found there was a substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of the Inmans’ land. However, we don’t know why. In Sultan, a New York case which involved running bamboo, another rhizomatous invasive plant, the court found a substantial interference with the plaintiffs’ use and enjoyment of their land. There the plaintiffs testified that bamboo shoots continually popped up their yard because of the infestation on the defendants’ property. Running bamboo was also sprouting under the plaintiffs’ deck. Both the defendants’ and plaintiffs’ experts agreed that bamboo was an invasive plant and that mowing and clipping could only “contain bamboo” but could not “eradicate” it. The court found the plaintiffs’ expert testimony credible that “the only effective means to eradicate and contain the bamboo is to excavate and remove the existing bamboo growth and to install a barrier.” Given this, the court ruled that letting the bamboo invade the plaintiffs’ property was a substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of their property.

Complicating any nuisance or tort action is a line of cases from different jurisdictions dealing with nuisances arising from “trees or other plant life.” A nice summary of these cases is provided in Lane v. W.J. Curry & Sons, 92 SW3d 355 (Tenn. 2002). Most of these cases deal with encroaching tree roots and branches.

Some of these cases adopt what’s known as the “Massachusetts rule” and are surprisingly reluctant to impose duties on the tree owner. See, e.g., Michalson v Nutting, 275 Mass 232, 175 NE 490 (1931) (holding a plaintiff’s only recourse was self-help to deal with the roots of a poplar tree that had plugged his sewer and cracked the foundation of his cellar). Eight states have formally adopted the Massachusetts rule. See Greenwald et al, note 12.

One exception to the Massachusetts rule noted in Michalson was for trees that are “noxious.” Thus, even in those states adopting the Massachusetts rule, a noxious tree could result in liability. What exactly is meant by a “noxious” tree or plant from these decisions is unclear. I did not find any cases that pinned this definition to the noxious weed or invasive species laws.

Some cases like Michalson indicate the tree or weed must be “poisonous” for the tree or weed to be considered noxious. In other cases, “noxious” just means it causes “actual damage” or poses an imminent risk of causing actual harm to the neighboring property. Cannon v. Dunn, 145 Ariz. 115, 700 P.2d 502 (Ariz. Ct. App. 1985). The standard of requiring a finding of “actual harm” or “an imminent danger” of actual harm to property “other than plant life” is also known as the “Hawaii Rule” as set forth in Whitesell v. Houlton, 632 P.2d 1077 (Ha. 1981). If the standard is just “actual harm” or an imminent risk thereof as in Cannon or Whitesell, the standard is not so different from the one in a typical nuisance claim.

New York is an interesting jurisdiction because there are nuisance cases that are the more traditional “tree root” cases and ones with identified invasive species like invasive knotweed and running bamboo such as in Inman and Sultan. In the tree root cases, even though New York does not follow the Massachusetts rule, the New York courts have been reluctant to award damages from harm caused to neighboring property in nuisance cases. See Iny v. Collom, 4 Misc 3d 1009 (S Ct NY 2006)(reversing an award of damages for tree root damage to a garage and requiring dismissal of action if defendant submitted proof of the offending tree’s removal); Loggia v. Grobe, 128 Misc.2d 973, 491 N.Y.S.2d 973 (D. Ct. 1985) (finding with regard to plaintiff’s damaged patio “although plaintiff has established property damage in the real sense, there is no proof of an interference with the use and enjoyment of land amounting to an injury in relation to a right of ownership in that land”). In contrast, in the invasive plant cases of Inman and Sultan, New York courts made substantial awards.

My belief is that even in states which have explicitly adopted the Massachusetts rule, courts will still favorably view nuisance claims against defendants who allow invasive species to encroach on neighboring properties. The reason is likely straightforward: trees are generally viewed as beneficial; whereas, invasive ones or invasive weeds as a class are not.

The second element in a nuisance action in New York and many other states, negligent or reckless conduct, is addressed next.

Conduct that Was Negligent or Reckless: The legal standard for negligent conduct is well-known. It has four components:

1. Duty

2. Breach

3. Causation

4. Damages

In a nuisance action, if a plaintiff has shown that there has been a substantial interference with the use and enjoyment of the plaintiff’s land, the first two elements of negligence – duty and breach – have effectively been proved.

Causation has two aspects, “causation in-fact” and proximate cause. “Causation in-fact” is a simple, “but-for” test. But for the defendant’s conduct, would the plaintiff have been harmed? Bear in mind that for knotweed or other invasive weeds, the plaintiff would typically not have to show that the defendant took affirmative actions such as planting the knotweed. In Inman, for example, it most likely was the defendant’s inaction in allowing the knotweed to spread from the defendant’s property to the plaintiff’s that was the basis for the claim.

Proximate cause can be a more complicated question. The standard asks whether the harmful result of the defendant’s conduct was reasonably foreseeable by the defendant. The classic case involving foreseeability is Palsgraf v. Long Island Railroad Co, 248 NY 339 (1928), with an opinion written by the renowned New York jurist, Benjamin Carzdozo. In Palsgraf, a railroad employee helped a passenger carrying a package onto a train. The passenger dropped the package, and the package exploded, injuring a woman. The court held that the railroad company was not liable because it was not reasonably foreseeable that the act of an employee helping a passenger with a package onto a train would cause an explosion.

In the running bamboo case from New York discussed earlier, Sultan, there really was not any issue of cause-in-fact or proximate cause. The defendant intentionally planted the bamboo near the property boundary and knew of its tendency to spread in “all directions.”

However, one can easily envision hypothetical situations where causation-in-fact may be at issue. For example, a knotweed infestation might straddle a property boundary. Can the plaintiff prove that either that the defendant planted the knotweed or that the knotweed infestation started on the defendant’s property? That is a causation-in-fact issue.

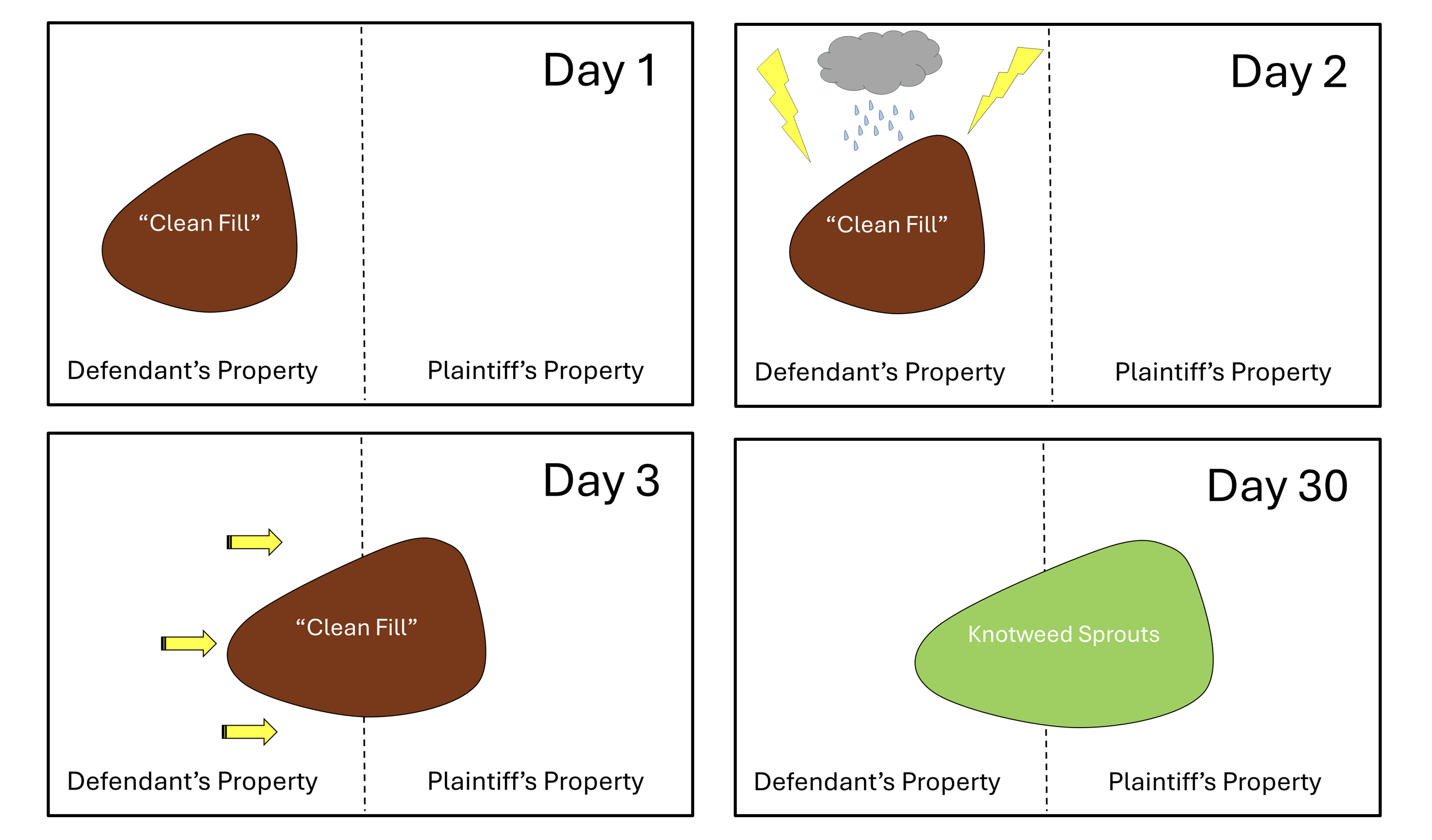

Proximate cause could also be in dispute. /image For example, assume a homeowner purchased and installed some fill near the property of a neighbor as shown in the image below. Soon after installation, rain washed some of the fill onto the neighbor’s property. Several weeks later invasive knotweed started growing in the area where the fill was located, including on the plaintiff’s property.

Here it would be easy to show causation in-fact: but for the homeowner’s purchase and installation of the fill, there wouldn’t have been contamination with knotweed propagules of the neighbor’s property. On proximate cause, the issue becomes more complicated. A key question would be where the defendant homeowner obtained the fill. If the defendant homeowner bought packaged soil from a garden store, it seems the homeowner would have a reasonable expectation that the soil was not contaminated with invasive weed propagules. In such a case, the plaintiff might have a better cause of action against the soil supplier. On the other hand, if the defendant homeowner got the fill from a nearby vacant lot, the likelihood of harm seems more foreseeable. Even though the defendant might not have known the soil was contaminated with invasive knotweed plant parts, it seems the defendant could have expected the soil from the vacant lot might contain weed propagules.

Reckless Conduct. With reckless conduct, the test for negligence must first be met. In addition, there has to be additional proof that the defendant acted in a dangerous way or with deliberate disregard for someone’s property. Reckless conduct could arise in a knotweed nuisance action, although it would likely be rare. One case where it could arise is in a scenario like the one discussed above. If a person sold soil knowing that it was contaminated with invasive knotweed propagules, that kind of conduct could be found to be reckless.

Damages. The scope of the damages in a nuisance or negligence action may be greater in scope than those available in the typical real estate transaction. As is made clear in Lane, for example, damages could include “the cost of restoring the property to its pre-nuisance condition, as well as damages for inconvenience, emotional distress, and injury to the use and enjoyment of the property.” Lane, 92 SW.3d at 361 (citing Pryor v. Willoughby, 36 S.W.3d 829, 831 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2000)).

In Sultan, the court awarded damages of $57,149.38 for the eradication of the bamboo on the plaintiffs’ property and the installation of a barrier to prevent future spread. This essentially put the plaintiffs there in the pre-nuisance position. In Inman the award of over $500,000 was more substantial. The sum was likely based on things other than just restoring the plaintiffs’ property to its pre-nuisance condition.

One might think emotional distress being caused by an invasion of weeds seems far-fetched. However, it doesn’t if you read accounts such as those in Henry Grabar’s article in Slate Magazine, “Oh No, Not Knotweed! (2019), of people being driven to suicide because of knotweed infestations in the United Kingdom.

In some states, for a plaintiff to recover damages for suffering emotional distress from a nuisance, there must be proof of physical injury. Bailey v. Shriberg, 576 N.E.2d 1377, 1380 (Mass. App. Ct. 1991). In other states such as California, this is not necessary. “Kornoff v. Kingsburg Cotton Oil Co., 45 Cal.2d 265, 288 P.2d 507 (Cal. 1955). The latter is the prevailing view. Therefore, in these states one could recover damages even for “personal inconvenience, discomfort, annoyance, anguish, or sickness,” without showing physical harm. Land Baron Investments v. Bonnie Springs Family LP, 131 Nev. Adv. Op. 69 (Sept. 17, 2015).

As mentioned, punitive damages could be recovered for reckless behavior. The Arkansas Supreme Court in National By-Products Inc. v. Searcy House Moving Co., 292 Ark. 491, 731 S.W.2d 194 (1987) found an award of punitive damages required evidence the “negligent party knew, or had reason to believe, that his act of negligence was about to inflict injury, and that he continued in his course with a conscious indifference to the consequences.” Florida has a statute on punitive damages that requires proof by “clear and convincing evidence” that the defendant was “personally guilty of intentional misconduct or gross negligence.” Florida Statutes Section 768.72 (2024).

Statute of Limitations and Continuing or Permanent Nuisances. States have different statutes of limitations periods for private nuisances. In Minnesota, for example, the limitation is 6 years. Minn. Stat. §561.01 (2024). In New York it is 3 years. New York Civil Practice Law & Rules (CVP) §214(4). The limitations periods are the same for trespass actions in Minnesota and New York.

In analyzing the running of the statute of limitations, it is critical to determine whether the nuisance is continuing or permanent. In California, if the defendant has the ability to stop or “abate” the nuisance, the nuisance is considered to be a “continuing nuisance.” King RE, “Chemical Contamination in California: a Continuing Nuisance,” 1997 Univ Chicago Legal Forum 483, 485. If the nuisance is a continuing one, then a new statute of limitations begins to run each day until the nuisance is abated. Thus, there effectively is no statute of limitations for continuing nuisances, but the plaintiff cannot recover future damages. See Lyles v. State of California, 153 Cal.App.4th 281, 291, 62 Cal.Rptr.3d 696 (2007).

With knotweed infestations, determining the running of the statute of limitations could be tricky. Most of an infestation can be abated. However, complete eradication, except at great expense, is probably impossible. Therefore, an invasive knotweed infestation has aspects of both a continuing and permanent nuisance.

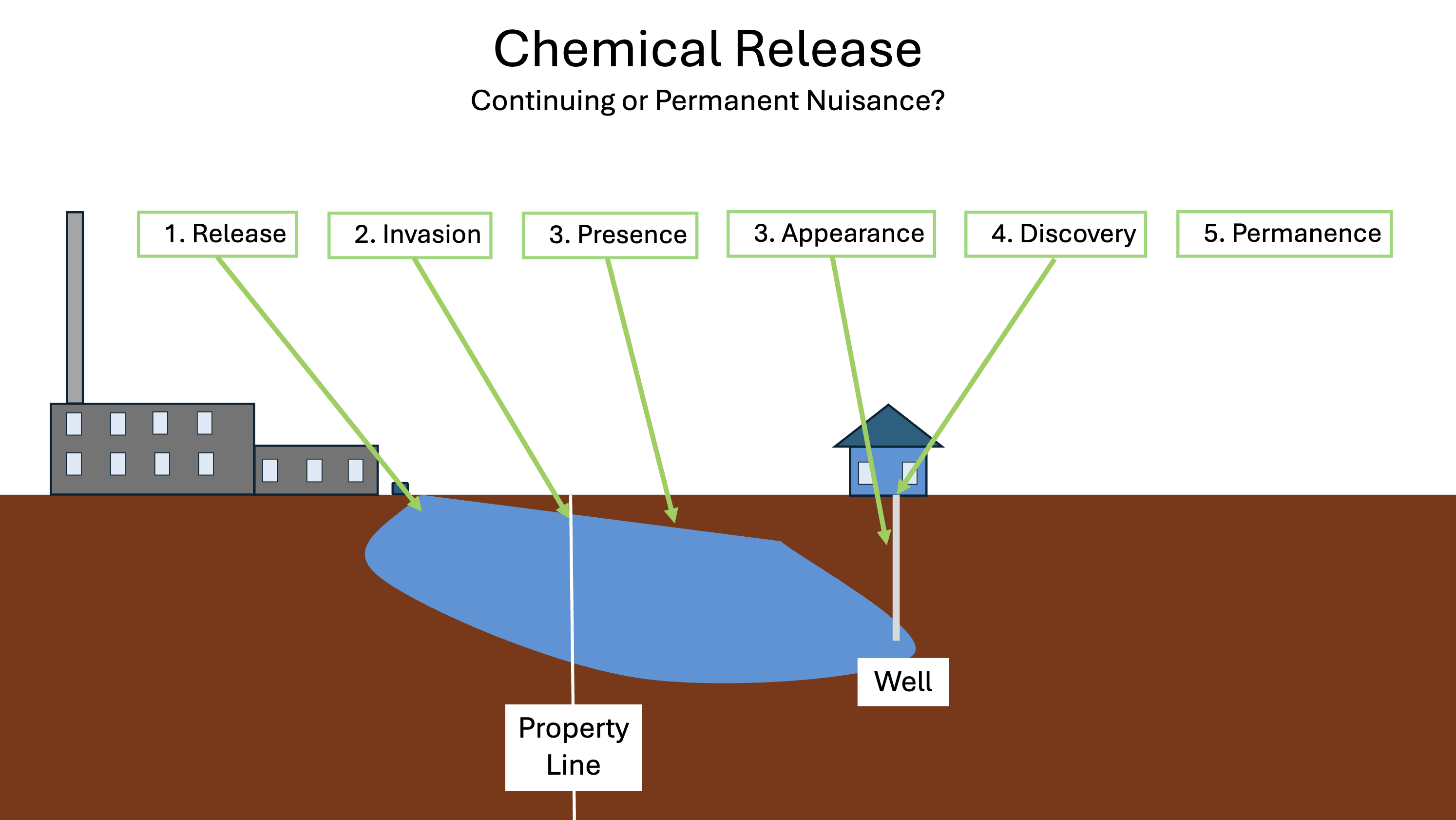

In the case law, I see six different rules which could control the running of the statute of limitations in negligence, nuisance, or trespass actions.

1. Release – Date of the release starts the clock.

Jalla v. Shell International Trading and Shipping Company [2023] UKSC 16 (case from the United Kingdom).

2. Invasion – Date when contaminant invaded the plaintiff’s property starts the clock.

Cook v. DeSoto Fuels, Inc., 169 S.W.3d 94, (mo. Ct. App. 2005) (Plaintiffs “are entitled to seek damages arising from any continued migration or seepage of contaminants onto their property within the five-year period preceding this lawsuit.)

3. Presence – The clock starts anytime during which the contaminant is on plaintiff’s property.

Hoery v. United States, 64 P.3d 214 (Colo 2013)(“For statute of limitations purposes, a claim would only accrue once the defendant abated the nuisance and removed the cause of damage.”)

4. Appearance – The clock starts when the damage becomes apparent.

Carnesville Block Co. v. Niagara Mohawk Power Corp., 175 A.D.2d 444, 445 (NY 3d Dept 1991).

5. Discovery – When the plaintiff discovered the contamination starts the clock.

42 U.S.C. § 9612(d)(2)(adopting a “discovery rule” for federal Superfund or natural resource damages claims).

6. Permanence – Can the contamination be abated at a reasonable cost? If not, the nuisance is permanent, and the clock starts from the release (i.e., same as number 1).

Da Mangini v Aerojet-General Corp., 12 Cal 4th 1087, 51 Cal Rptr 2d 272 (1996).

Note that in the Sultan case discussed earlier, for the statute of limitations, the court followed the same rule set forth in Hoery under rule 3 above. However, for the negligence claim it followed rule 4 above. Under both of these rules and for all the pending claims, the court found that the defendant had not proved a violation of the statute of limitations.

Potential Litigation Hotspots. Is litigation based on knotweed infestations likely to soar in the coming years in the United States? As I see it, there are these potential hotspots:

Contaminated Fill. This is what precipitated the lawsuit in Trites v. Cricones. As I noted in Part 2 of these presentations, the contaminated fill in that case may have been spread onto 27 different lots in the property development. Use of contaminated fill for landscaping work is not uncommon. I have talked with Green Shoots customers who have had fill contaminated with invasive knotweed brought onto their property.

Whoever transports contaminated fill could be liable in states with noxious weed or invasive species laws like Colorado (Eradication requirement), Minnesota (Prohibited Control requirement), or New York (Prohibited transport requirement). In these and other states, the transportation of live knotweed plant parts, “propagules,” would be illegal. And, this would be a nuisance per se as discussed above. See, e.g., New Orleans v. Liberty Shop, 157 La. 26, 101 So. 798, 799 (1924)(a leading case, holding that a violation of a zoning ordinance is a nuisance per se).

Emotional Distress. The Trites claimed intentional infliction of emotional distress. The jury in Trites found for the defendants on this issue. It does not appear that the Inmans sought damages for the infliction of emotional distress. If personal inconvenience, discomfort, annoyance can be bases for an award of damages for emotional distress without proof of physical harm, however, it seems likely that more plaintiffs will be successful in winning damages for the infliction of emotional distress.

Septic Systems. I list this as a possible hotspot because, as invasive knotweed spreads across the United States, more and more septic systems will be affected. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, twenty-five percent of homeowners have septic systems. Given the spreading nature of invasive knotweed, it only seems to be a matter of time before more systems are affected. In such cases, there would be ready proof of harm to physical structures and repair costs.

Legal Liability and Invasive Knotweed in the United States – Part 2 of 3

The most recent case concerning invasive knotweed was just decided by the Massachusetts Appeals Court, Trites v. Cricones, Slip Op No. 23-P-884 (Mass App Ct 2025). In this case, the homeowners, the Trites, brought an action against the developer and seller, Cricones and his company Reedy Meadow, LLC. The Trites claimed that Cricones and Reedy Meadows failed to disclose the presence of invasive knotweed (as well as glass and other debris mixed in with the soil) on the purchased property. The trial court found the defendants engaged in unfair and deceptive practice under the Massachusetts Consumer Protection Act , chapter 93A. The trial court awarded the Trites $186,000 in damages and added reasonable attorney’s fees. The Appeals Court affirmed the judgment.

According to the Massachusetts Appeals Court the plaintiffs, the Trites, had to show under chapter 93A:

- the defendants knew hazardous material contaminated the property;

- the defendant did not disclose the contamination; and

- the plaintiff would not have purchased the property had the plaintiff known of the contamination.

As to whether Cricones knew about the contamination, the court identified several facts. Before the sale, Cricones had spread topsoil in the housing development, even though he knew the soil was contaminated with invasive knotweed. In addition, he had been warned by a subcontractor not to use the contaminated loam because it contained viable invasive knotweed plant parts.

Cricones also did not disclose the contamination to the Trites. Finally, the Appeals Court found that it was “clear that the Trites would not have purchased the property had they known about the contamination of its soil.” If the plaintiff knew about the contamination before the purchase, the defendants could have avoided liability. As the court observed, however, the Trites “bought the house before the knotweed growing season began, and snow and hydroseed prevented them and their inspector from detecting contaminants in the soil before purchase.” The court therefore affirmed the trial court ruling on chapter 93A liability.

The Rest of the U.S. – Invasive knotweed and Its Effect on Real Estate Transactions

How does the Trites case fit within the nationwide landscape of residential real estate law? It is important to remember that Trites was decided under a state consumer law. The outcome could be different in other states which do not have consumer laws that are as far-reaching as Massachusetts.

In most states, the laws which govern home sales are a combination of judge made law (the “common law”) and statutory law. The legal doctrines which govern home sales broadly fit within the four categories discussed below.

1. Warranty of Habitability. This warranty can have its origin in statute, the common law, or a combination of the two. Some states may require the seller to include the warranty in the sales contract. The warranty typically only applies to new homes.

In its purest form, the warranty of habitability imposes strict liability. There is no question of whether the defect in question is obvious or hidden. There is also no question about the seller’s or the buyer’s awareness of any defects.

New Jersey was the first state to adopt a strict liability standard via a court decision. See Schipper v. Levitt and Sons, Inc., 44 N.J. 70 207 A.2d 314 (1965). California now has common law and statutory protections that make builders of new homes strictly liable for certain construction defects. See Kriegler v. Eichler Homes, Inc., 269 Cal. App. 2d 224, 227 (1969). California Right to Repair Act, Civil Code §§ 895 – 945.

This warranty holds the seller responsible for any “material defect” in the property sold. It appears that every state, no matter which of the four doctrines the state has adopted, requires for a defect to be “material,” for it to be actionable.

With regard to what is a “material defect,” there are really two questions:

- What is a defect? Or, what kinds of defects are considered?

- What it material?

What kinds of defects are considered? According to the International Association of Home Inspectors Standards of Practice for Performing a General Home Inspection (revised October 2022), Standard 1.2 a material defect “is a specific issue with a system or component of a residential property that may have a significant, adverse impact on the value of the property, or that poses an unreasonable risk to people.”

Is the green space that the invasive knotweed infests considered “a system or component of residential property”? Under the international standard, it doesn’t seem to be. “Systems” and “components” are all connected with physical structures: roof, exterior, basement, heating, cooling, plumbing, etc. The inspector is supposed to inspect “vegetation, surface drainage, retaining walls and grading of the property, where they may adversely affect the structure due to moisture intrusion.” Section 3.2,I.I. However, the inspector does not have to “inspect or identify geological, geotechnical, hydrological or soil conditions.” 3.2, IV.C.

One law review article also suggests that, at least with the warranty of habitability, the protection does not extend beyond the physical structures and its systems. Shisler RH, Caveat Emptor Is Alive And Well And Living In New Jersey: A New Disclosure Statue Inadequately Protects Residential Buyers, 8 Fordham Environ Law Rev, 181, 192-193 (1996).

Assuming that a defect does extend to defects beyond those in the physical structures, what makes a defect “material”? Generally, a fact is material if a reasonable person would attach “importance” to its existence or nonexistence in choosing a course of action in the transaction in question. Restatement (Second) of Torts § 538 (1989). The International Building Code says a defect has to have a “significant, adverse impact” on the property value. Massachusetts, as noted above, seems to have an even higher standard for “materiality.” Massachusetts under chapter 93A required a showing “the plaintiff would not have purchased the property had the plaintiff known of the contamination.” Trites, Slip op at 16. In short, there is no generally accepted definition of what a material defect is with regard to real estate.

To show a knotweed infestation was a material defect, plaintiffs can submit proof such as the following:

- the buyer’s use and enjoyment of green space – recreating, gardening, landscaping would be or was affected;

- the effect of invasive knotweed on property values (likely expert testimony); and

- the effect (actual or potential) of invasive knotweed on physical structures (likely expert testimony).

Defendants can argue that the presence of invasive knotweed is not a “material defect.” They could point to the fact that home inspectors are not required to look for it. This fact alone may suggest non-materiality. After all, inspectors should inspect for things that are important to homeowners.

How long does the warranty of habitability last? In some states, like Illinois, this warranty is a common law doctrine, and the warranty has no specific duration. Illinois courts generally require that defects be reported within a “reasonable time” after discovery. In Arizona, it appears to last at maximum, eight years. Zambrano v. M & RC II, LLC, 254 Ariz. 53 (2022). Warranties may be limited to the original purchasers of new homes. Dallon, “Theories of Real Estate Broker Liability and the Effect of the “As Is” Clause, 54 Florida Law Rev 2002, 395, 408 note 66. However, as Zambrano makes clear, that is not the case in Arizona.

2. Disclosure of Known Defects. Most states require a disclosure of known “defects.” This doctrine often applies regardless whether the transaction involves new or old construction or a professional builder. One example is Minnesota law, Minn. Stat. Sec 513.55 (2024). Minnesota law requires the seller to identify “all material facts of which the seller is aware that could adversely and significantly affect: (1) an ordinary buyer’s use and enjoyment of the property; or, (2) any intended use of the property of which the seller is aware.” Note that this standard requires the disclosure of both patent (i.e., “obvious”) and latent (i.e., hidden) defects. Interestingly, this Minnesota law does not on its face look to the effect of the defect on “property values” but instead looks at “use and enjoyment of the property” by the purchaser. Here plaintiffs might have to argue that the invasive knotweed affected their “use and enjoyment of the property” in at least two ways: first, it required them to work or pay for work to control the knotweed; second, it affected their “use and enjoyment” because the knotweed depreciated property value and potentially made the property harder to sell.

“all material facts of which the seller is aware that could adversely and significantly affect: (1) an ordinary buyer’s use and enjoyment of the property; or, (2) any intended use of the property of which the seller is aware.”

Minnesota Statute Section 513.55 (2024).

In at least two respects, the duty to disclose “known defects” may be broader than the warranty of habitability. First, it applies to both new and used homes. This is important since new home sales made up only 30% of home sales in 2024 in the U.S.

Second, the requirement to disclose “known defects,” unlike the warranty of habitability, may extend beyond just the physical structures. There is not much reported case law on this. However, such defects may be actionable under the duty to disclose known defects. Shisler RH, Caveat Emptor Is Alive And Well And Living In New Jersey: A New Disclosure Statue Inadequately Protects Residential Buyers, 8 Fordham Environ Law Rev, 181, 192-193 (1996).

3. Disclosure of “Latent” or “Hidden” Defects. Some states only require the disclosure of hidden defects. A hidden defect is “one which could not be discovered by reasonable and customary observation or inspection.” Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute, “Latent Defect” (Updated June 2020). For example, in Maryland even if a seller and buyer agree to an “as is” sale of real property, the seller still must disclose latent defects the seller is aware of.

With invasive knotweed, this doctrine raises all sorts of questions. In Trites, the plaintiff were not required to prove the defects were hidden. Nonetheless, the plaintiffs offered proof that they were: The inspector testified that it was not customary to inspect for invasive knotweed, and so the inspector did not inspect for it. Moreover, the inspection was conducted in winter after the lawn had been hydroseeded. Both of these hid the presence of the knotweed.

What if the invasive knotweed was growing in plain sight? Under normal circumstances a defect that is visible would be “patent” or “obvious.” However, an argument could be made that, because invasive knotweed is not well-recognized hazard in the U.S., the presence of it is not a defect which could be “discovered by reasonable and customary observation or inspection.”

4. Caveat Emptor or “Buyer Beware.” Some states do not require any disclosures in home sales (other than federally mandated ones). Interestingly, Massachusetts, the state in which the Trites case arose, is one of these. In these states a private, non-commercial seller would not have to make any disclosure related to invasive knotweed. Thus, in Massachusetts a seller was not held liable even though the seller knew the house was infested with termites. Swinton v. Whitinsville Savings Bank, 311 Mass. 677, 42 N.E.2d 808 (Mass. 1942). A critical reason why caveat emptor did not apply in Trites was that Cricones’s development company, Reedy Meadow, LLC, had to comply with the state’s consumer laws and was also sued. If the Trites had bought their house from a private party not in the real estate business, the Trites likely would not have prevailed.

There is an exception to caveat emptor. If a seller actively conceals a defect, this can constitute fraud which is a known exception to caveat emptor. This concealment has to be more than mere silence. In one New York case, for example, the seller was found to face potential liability because the seller allegedly covered rotted wood with new wood to hide areas where water infiltrated. Striplin v. AC&E Home Inspection Corp., 2023 N.Y. Slip Op. 03720 (2d Dept. July 5, 2023).

In Trites there was no proof of fraud. However, the line between active concealment and just spiffing up the property could be a fine one. For example, if a seller has knotweed on the property and cuts it down and covers the location with mulch and maybe plants some ornamental plants, is this “active concealment”?

Advice to Home Buyers and Sellers

Ultimately, advice to home sellers can be boiled down to this. First, control the invasive knotweed. Even if the knotweed cannot be fully eradicated before sale, a site with scattered small knotweed plants is far different from a dense patch with twelve-foot-tall aerial shoots.

Second, disclosure of a knotweed infestation goes a long way toward reducing your potential liability. If Cricones had indicated to the Trites that there was knotweed on the property, he and his company would have prevailed. Even in states with the strictest liability, a full disclosure may absolve a seller of potential liability. After all, if a buyer buys a home knowing the lot has invasive knotweed on it, the buyer would have more difficulty claiming the knotweed on the property was a material defect. The decrease in value caused by the knotweed patch was presumably incorporated in the sales price (or was so immaterial that the presence of knotweed didn’t affect the price).

If you are a buyer, especially in an area with heavy knotweed infestations, you should ask the seller about any invasive knotweed. This would be especially important on a large piece of property that cannot be thoroughly inspected. Be aware, however, that many sellers may legitimately not know what it is. Ask your attorney about getting written assurances. Regardless, you or someone you hire should inspect the property. If it’s winter, look for the tell-tale reddish colored stems.